Green Utopianism & Environmental Outcomes

Herescope Vintage Article Series[1]

|

| Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez launches her Green New Deal (Source) |

The following 1993 article explains the contents of the proposed Green New Deal in the United States Congress by the newly-elected Rep. Acasio-Cortez {AOC]. There has been considerable debate already about its controversial FAQs which will have global repercussions.

This vintage 1993 article[2] describes how the education reform agenda, including Outcome-Based Education (OBE) of the late 1980s through the 1990s, integrated and infused a radically new spirituality-based environmental agenda into academic curriculum and assessment tests. Young adults in America who attended public schools have been inculcated with this eco-spiritual worldview. Perhaps this fact explains AOC’s current proposal.

Many Christian parents, while concerned about the environment, have opposed the extreme tenets of global education, which taught students a New Age New World Order. [3]

The Green Future Envisioned

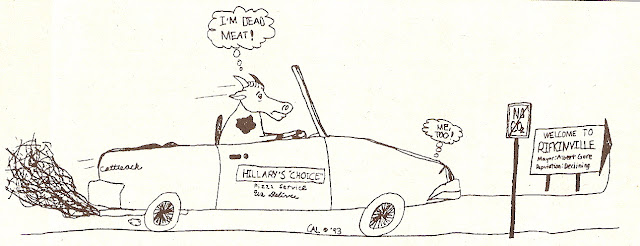

The problem with cows and cars, it seems, is with their… well, er… emissions. Both are supposedly responsible for wreaking havoc on the planet Earth (spelled with a capital “E” to suggest respect and “reverence”) because of their CO2 output–for one a matter of life, for the other a manner of mechanization.

They both have to go. This means tractors, too, of course. The goals for sustainability, according to the latest environmental craze (which we have dubbed “Green Utopianianism”), requires an abandonment of modern material affluence, a transfer of wealth to third world countries and, unmistakably, a return to the manual plow accompanied by a vegetarian diet.

Where can one find such utopian nonsense? It is popping up with increasing frequency in mainstream publications and credible-sounding scientific documents. Jeremy Rifkin’s “Beyond Beef” campaign and Al Gore’s recent book, Earth in the Balance (1992), have lent the necessary pizzazz to launch a massive public relations campaign about the environmental hazards of these CO2 emissions (that’s “gas” for the folks in Rio Linda, California).

The education establishment, prone to jumping on the latest bandwagon, is going great guns for environmental education. Educators are frequently puzzled and amazed when parents object to environmental and global curriculums and outcomes. What could be wrong with that, they ask. We recommend they read the literature.

The Rave Review

We found the abolishment of the cow and car through reading an Iowa Department of Education document. Several years ago, in a publication entitled Social Studies Horizons (Fall 1990), just such a utopian book was given a rave review. This book, originally entitled The Future as if it Really Mattered, was recently re-issued under a new title–Toward A Sustainable Society: An Economic, Social and Environmental Agenda for Our Children’s Future by James Garbarino. The title says it all. It is quite an agenda!

Here is the rave review from the Iowa Department of Education:

Excerpts from a book that is a class of practical wisdom on what a sustainable society is, why we need to move to a sustainable society, and what a sustainable society might look like. It is this kind of thinking we need to consider as we move toward transforming the social studies. It seems to me that teaching the “transformational economics” of sustainability would be a much more empowering and enlivening process for our students than the textbook-mired “dismal science” approach to economics that has been the norm. (Iowa DE, Social Studies Horizons, p. 4)

If you think sustainability is just a nice new term to describe more environmentally responsible farming methods, think again. Sustainability, at least to the new Green Utopians, is an entire restructuring of the way humans live on the planet, and is the new prime directive for the survival of species (man only somewhat included).

The 1990 Iowa Department of Education publication quoted Garbarino, who claimed:

“This enjoyment of owning, having, spending, buying, and consuming is a serious threat. It threatens our relationship with the Earth and our relationships with each other, particularly in our families and in our efforts to preserve the resources necessary for social welfare systems. It cannibalized the planet, undermines the spiritual order, and leaves us scrambling to fill the social and spiritual void with positions. It is an addiction pure and simple… and our chances of making the transition to a sustainable society depend upon our overcoming it.” (Social Studies Horizons, p. 4)

The major chore for humans on Garbarino’s anthropomorphic Earth is to make the transition to sustainability. But, just what does HE mean by this? What is the agenda of the new Green Utopians?

Utopian Sustainability

Garbarino’s transition to sustainability is a process long on ideology and short on specifics, in typical utopian fashion. Garbarino states:

Our goal, remember, is the creation of a more SUSTAINABLE human community based on competent social welfare systems, just and satisfying employment, reliance on the nonmonetarized economy for meeting many needs, and a political climate that encourages cultural evolution and human dignity. (Towards a Sustainable Society, p. 162)

Garbarino identifies himself as a utopian throughout the book. His optimistic view of the future is dependent upon his faith that the human race will accept stringent population control measures, severely limited transportation and trade, earth-friendly housing, local neighborhood food and energy production, and government-regulated health and social welfare services. The seriousness of our common future is enough to warrant this massive overhaul of the Western lifestyle.

Our Not-So-Rave Review

The preface of Garbarino’s book (page ix) gives credit to Aurelio Peccei and the Club of Rome for the “wealth of ideas and information about the prospects for a sustainable society.” The Club of Rome is best known for its earth-shattering GLOBAL 2000 report, Limits to Growth, issued in 1972 calling for massive world-wide population control measures and many other controversial plans. The Club of Rome is one of those international organizations that the extreme Left esteems (including the national media) and the extreme Right views as one of “those” conspiratorial groups.

The Club of Rome does not advocate for a mainstream, reasonable approach to environmental stewardship. Not by any stretch of the imagination. It is an indisputable fact that the Club of Rome is tied closely to the wacky international New Age groups known as Planetary Citizens. Planetary Citizens sponsored a “1990 World Symposium on Interspecies & Interdimensional Communication.” (This means communicating with species not of this world!) Aurelio Peccei’s name has appeared on Planetary Citizens letterhead.

A Return to the Plow

Tractors will go the way of the car and the cow. Manual high-tech plows are the wave of the new utopian future.

The plow developed by the Schumacher-inspired Intermediate Technology Group is a good example [of appropriate technology]. It relieves the backbreaking burden of working an oxen-powered plow, but it is not a conventional tractor. In their clever arrangement, a small engine pulls a plow across a field using a wire, while two farmers use their skill and strength to guide it. The result is better plowing with a less expensive tool and provision of meaningful work. (p. 223)

This utopian vision of a new society includes agricultural cooperatives, a cashless economy, and women working at home at gardening chores to provide food for their households and communities. “Household and community gardens can successfully produce fruits and vegetables and in some cases even grain.” (p. 231-2) Concurrent with these recommendations is the elimination of most global trade because of its relationship to transportation (which produces CO2). Everything must be produced locally.

Eating meat is not included in the book. “The massive concentrations of cattle excrement produce large amounts of methane,” claims Garbarino in Rifkin-like fashion. Presumably the cow is regulated to a position of prominence in society, perhaps even veneration. If the cow isn’t good for food, and not an “appropriate” technological substitute for the tractor for use with plows, then perhaps the Green Utopians of the future will hang garlands of flowers about their necks!

Car Crimes

Garbarino wrote:

“Using a car to accomplish daily tasks that could be done without one is a misdemeanor against the Earth and posterity. Social policies that encourage driving and discourage walking are crimes against the planet.” (p. 221)

The term for this new kind of crime in Green Utopia is “bioeconomic crime” according to Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, who is further quoted on the matter of automobiles:

“Every time we produce a Cadillac, we irrevocably destroy an amount of low entropy that could otherwise be used for producing a plow or a spade. In other words, every time we produce a Cadillac, we do it at the cost of decreasing the number of human lives in the future.” (p. 135)

This type of logic, which ties Western consumption to the future destruction of the Earth, is the drum-beat of Garbarino’s book. It explains the reasoning behind the original version of the Iowa Department of Education’s controversial Catalogue of Global Education Classroom Activities, Lesson Plans, and Resources (1990). This curriculum manual, in addition to containing a reference to James Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis (that earth is both an entity and a deity), included a Social Studies exercise for grades 4-6 which linked eating red meat to the destruction of the tropical rainforest:

Calculate the amount of meat eaten by a person in the U.S. per year; translate to number of animals. How much energy and grain are used to produce this meat? How many trees in the tropical rainforest are destroyed to produce this meat? (Catalogue, p. 26)

For Garbarino and the Green Utopians, automobile-based urbanization is a major culprit in the anti-sustainable modern lifestyle. “Suburbs are not conducive to sustainable patterns.” (p. 166) Suburbs allow people to live far away from where they work and shop. Suburbs depend upon the car, or other forms of transit. Suburbs are not an acceptable alternative. So what, then, is the utopian alternative?

The Abolition of Patriarchy

Garbarino would like to redefine the family in the context of community, what he terms social welfare systems for a sustainable society. His ideas parallel those of the social engineers. He would make community be parent:

Communities should share joint custody of children with parents… we can require `registration and inspection’ of young children so that the community can monitor child development and not lose track of the children for which it is responsible. (p. 245)

Garbarino also calls for a parenting license. Family roles are redefined, too.

We need to end masculine domination both in the family and in society, so that we can create a cultural climate in which the sustainable society can exist. (p. 66)

Patriarchy is a threat to the planet, according to Garbarino. He devotes and entire chapter to this subject because he believes we need to have a more feminine ethic to survive. His book has probably never been fully embraced by the feminists, however, because he believes women should be out working in the gardens and fields producing the household’s food!

Garbarino’s design for sustainable social welfare systems for families are nearly identical to the education reform efforts, including parents as “partners”, a “community level organization… for transportation systems, formal education, industrial enterprise, and the like.” (p. 222) Although he does not specifically identify the school as the “hub” of the community structure (as we have seen in other education reform writings), it is clear that the new environmentally-correct society will be managed by grouping people into small neighborhood communities–almost completely self-sufficient in food production and other life needs, but requiring intimate governmental managing of their personal and family lives.

Mandatory Population Controls

Garbarino writes:

To achieve a stable population, countries will have to establish a comprehensive and pervasive family planning program and carefully monitor immigration. At minimum, accomplishing this will require incentives for keeping family size at the replacement level, penalties for exceeding that level, and complete access to contraception. It will mean that family size will be limited to two children. (p. 228)

Family planning, the obligatory two children, is the cornerstone of Garbarino’s sustainable society. He lauds the Chinese example, despite its oppressiveness (penalties) and slaughter (mandatory abortions). In fact, rewards and penalties for ecologically responsible procreation are a key component to Garbarino’s ideal society. He views children as consumers of scare resources, more mouths to feed on a crowded planet.

Garbarino consistently speaks of children in terms of economics (human capital?):

Children are the currency of family life…” (p. 180)

Limiting the size of specific families may turn children into an economic commodity, if people can sell their rights to bear them. (p. 84)

Children are an economic benefit in the households, neighborhoods, and communities that rely upon human labor rather than non-renewable energy and materials to produce food and provide utilities. (p. 79)

Cashless Economics

A radical new economic order is interwoven throughout the entire text of the book. Garbarino’s economics calls for a cashless society and a new kind of economics that accurately accounts for the damage done to the environment. The price of every item must calculate the cost in terms of environmental destruction, especially nonrenewable resources like gasoline and oil.

Free enterprise is the villain to the world’s environmental woes. It is responsible for the destruction of the planet according to Garbarino and he utterly dismisses it as an option or a solution. The current “economic order and its cultural baggage are major obstacles in the transition to a sustainable society.” (p. 116) Reading Garbarino does not make one feel comfortable about Gorbachev heading up the new world effort for this Green Utopian (his international Green Cross environmental effort). The abolishment of free enterprise has always been at the forefront of the communist agenda.

Severe limits to world trade are called for by Garbarino:

“In a sustainable system, world trade would be limited to two domains. The first is ideas, technology, and artistic creations and the people necessary to communicate them. The second is material goods needed to meet basic human needs or to dramatically enhance human experience in ways unavailable locally. Most world trade today fails to meet either criterion.” (p. 152)

It is not clear why artistic creations are given such a high priority for trade! The National Endowment for the Arts will appreciate this recommendation.

Voluntary Poverty

A total and complete reduction in the modern American affluent lifestyle is called for. “A relatively poor American family typically uses less of the world’s resources than an affluent American family, but it still consumes much more than an Indian family that lives at subsistence level.” (p. 85) Therefore, Garbarino concludes, that only reasonable solution is this: “as the world’s leading consumer…. [the United States] has a special obligation to reduce its demands for resources to a level that is domestically sustainable.” (p. 89-90)

Garbarino’s ideas about what constitutes “sustainable” and the average American’s are radically different. He links American consumerism to every threat to the planet. It is not unlike the Iowa Global Education exercise for Home Economics students grades 9-12: “Seek connections between U.S. consumer and eating habits and the presence of malnutrition worldwide.” (Catalogue, p. 36)

A Riceville, Iowa, sophomore English class was given a “Simplicity Survey” as part of The Thoreau Project. The test sheds considerable light on the extent to which Garbarino’s radical ideas about sustainability have infiltrated classroom curriculum. Here are a few sample “commitments” that students had to make on the survey:

- I and/or my family will own no more than three sets of clothes and three pairs of shoes per person.

- I and/or my family will own only one automobile.

- My family and/or I will eat less meat, more vegetables and fruits, and no white sugar.

- My family and/or I will make our own simple personal products–such as, deodorant, soap, toothpaste–from old historical recipes.

- My family and/or I will learn to do almost everything for ourselves: cleaning, baking, repairing, building, etc.

This survey is a good indication of how Outcome-Based Education will function. If the child dos not score at a high enough “committed” level, the “teacher may ask you to retake this survey in order to see if the unit changes your commitment.” In other words, if the child doesn’t display the correct attitudes about this radical form of sustainability, they may have to re-take the test to see if their attitudes were changed!

The New Religion

To break our addiction to free enterprise, material consumption, and freedom in general, Garbarino calls for some new values. It is here that we begin to see the link between his Green Utopian view of a sustainable society and the strange-sounding ethical values contained in the new educational outcomes being promoted across the country. Garbarino cites Amitai Etzioni, saying that he “links consumerism, the work ethic, and cultural patriotism. This is a linkage we must break, replacing it with a combination of passionate commitment to a humane social environment and rejection of materialism as an end rather than a very limited means.” (p. 100) The old values have to go, to be replaced by a new ethic. These new values necessarily entail a new religion.

You may have guessed it–we need to form a relationship with the Earth. We are not told exactly HOW one goes about forming this new “relationship.” Hugging trees is good for a start–we need to “speak to the trees and listen to the birds.” (p. 226) Presumably, this new anthropomorphic view of Mother Earth is the new religion. Garbarino describes it this way: “A reformed human family emphasizing equity and harmony… is a good model to follow in establishing our relationship with the Earth.” (p. 99)

Like many of the other new Green Utopians (Al Gore, especially), Garbarino denigrates Christianity because it elevates man above nature:

“…Christianity was an ecological regression compared with the primitive animist impulse that emphasized the spiritual integrity of existence, the commonality of being, which demanded respect for the trees, the waters, the plants, the animals–for the Earth as a whole.” (p. 98)

Garbarino would replace big, bad Christianity with eastern mysticism.

“Buddhism teaches that material goods are only a means of achieving personal well-being. Consuming for its own sake has no value.” (p. 99)

And, here is a big admission: “Primitive animism has more in common with emerging ecological science, although other religious traditions can also accommodate it.” (p. 98-99) This admission may serve to explain the recent upsurge of religious indoctrination in environmental and global education curriculums. It also explains the including of native American Indian ritualistic rites in children’s curriculums.

Garbarino advocates for this new (old) earth-centered religion. But what of other religions? What will happen to freedom of religion under this utopian system? “Freedom will be absolute in the realm of ideas and expression but minimal in the domains of environmentally threatening behavior.” You can believe whatever you like, but your actions cannot harm the environment, however that comes to be defined. In fact, the environment reigns supreme in Green Utopia. The Earth’s needs (real or perceived) are paramount to human needs and human rights.

The New Green “Outcomes”

To achieve this Green Utopia requires that human beings accept a new system of ethics, one that values the Earth. Garbarino suggests that if “we can forge this link between personal and public concerns, we will be able to harness the motivating power of the family in transforming Spaceship Earth.” (p. 67) The current classroom emphases on environmental and global education are prime examples of this. Making small children feel responsible for the survival of the planet is one of the mechanisms for forging this link. “Children… need… to develop a sense of kinship with nature.” (p. 169)

Reversing biases “that currently discourage reusability, manual labor, and self reliance” (p. 205) is one of the goals for educating the public. This means that it is absolutely essential that public attitudes and values be altered to fit the new environmental crisis worldview of the future, complete with utopian solutions.

Amazingly, Garbarino’s book contains language almost identical to an outcome seen state by state across America in the new push for outcome-based education. “Socialization to adulthood means acquiring the skills and attitudes necessary to assume full responsibility in the work place, the home, and the community.” (p. 206) Iowa’s World Class Schools document states: “A world-class education will equip students to live, work and compete as successful citizens in a global society.” (p. 5)

In light of Garbarino’s Green Utopia, state by state comparisons of nearly identical outcome-based language takes on new significance. The language that educators are struggling to define is easily managed by the environmental fringe. In fact, William Spady, the father of modern OBE, has written “A fragile and vulnerable global environment… requires altering economic consumption patterns and quality of life standards, and taking collective responsibility for promoting health and wellness.” (Spady and Marshall, 1990)

In the new Green Utopia, social abilities are of prime importance. Garbarino gives primacy to social development rather than technological issues: “social changes, not technological fixes, are the primary vehicle for averting disaster and placing humanity on sustainable ecological and socioeconomic footing.” (p. 21) Because of this de-emphasis on technology, he believes that children

must become adept at language, body control, morality, reasoning, emotional expressiveness, and interpersonal relations. Unless they do, they become a burden–to their families, to our society, and even to themselves. (p. 105)

The belief system of the Green Utopians explains the national pressure to have attitudinal, behavioral and value-laden outcomes. It also explains the vacuum of solid academics. Reading, writing and arithmetic will no longer solve the world’s problems. The crisis is too complex. Humans must be taught to adjust and adapt instead. Garbarino does not stake his future hopes in technological development and man’s potential to develop scientific solutions for the complex environmental crisis. The only hope that he sees is sustainability.

Another nationally popular outcome has to do with diversity. Garbarino explains why this is so necessary: “Cultural diversity is as important as biological diversity in enhancing evolutionary resilience and human progress.” At least for some, “diversity” has much more to do with their religious beliefs in evolution of mankind than it has to do with protecting the human rights of religious and ethnic groups. Cultural diversity, in the form of multicultural education, often promotes ritualistic pagan practices that enhance a feeling of connectedness with the Earth.

Those who oppose the teaching of this new religion of interconnectedness with nature are labeled “racists.” When Davenport, Iowa, school board member Elaine Rathmann challenged a “Multi-Cultural Week” as mere “political indoctrination and social reform” she was publicly charged in the local press with racism.

The New Green Utopian Classroom

A recent article by Barbara Melz of the Boston Globe appeared in the Des Moines Register (6/6/93, p. 3E). Melz details the vulnerability of children to emotional manipulation in areas of environmentalism. She quotes from a book by Lynne Dumas (Talking with Your Child about a Troubled World, Fawcett Columbine): “Everything becomes a personal issue for kids, everything gets related in their minds to their own safety.”

The article goes on to give a poignant example of how vulnerable children can be to this type of education:

This is especially true of environmental issues, she says. From the earliest ages, children relate to animals and nature in a kind of magical way. `TV shots of oil-soaked birds and seals, whales trapped on a beach, endangered dolphins all these kinds of things can be very upsetting to them. They can react with an intensity that surprises parents,’ she says… solid waste disposal is an issue many school-age children glom on to in a very concrete way. `They see how much trash they produce in their own house. So here’s their worry: If everyone’s house makes this much trash, what will happen? Will there be enough room for me to live in the world?'”

Are children being educated or indoctrinated? Is it fair to burden them with feelings of guilt and responsibility based on the perceived crisis of the Green Utopians?

Only One Choice

A thorough reading of Garbarino’s book, especially in the context of other works by the new Green Utopians, creates the crisis and then presents the solution. His crisis is an out-of-control world population problem compounded by scarce resources. His worldview is clearly founded on the Club of Rome Global 2000 report. Garbarino has a limited view of human potential, technological innovation, the value of free enterprise, or ingenuity. However, there are serious questions about the scientific and rational validity of the entire so-called species.

The only politically-correct technology for the Green Utopians is apparently the computer, probably because of its ability to control human behavior through the charting actions and attitudes. The greater good of society and the seriousness of the threat against the planet would likely justify a central data bank to monitor each citizen according to the logic of Green Utopians.

Garbarino’s solution is a return to third-world subsistence living. Garbarino doesn’t say this directly. One must read between the lines and come to understand that abolishing cows and cars, transportation and trade, free enterprise and a market economy, and certain basic human freedoms in matters related to religion and procreation can only mean an international totalitarian society. Granted, Garbarino, the consummate Green Utopian, objects to this (totalitarianism) and feigns to distance himself from the nastiness of it all. Yet his proposals can mean nothing else.

The New Green World View

To explain sustainability, Garbarino gives an extensive quote from Voluntary Simplicity by Duane Elgin, in which Ram Dass–“a Western-style intellectual turned Eastern-style mystic”–tells a story about an ideal society. It sheds much light on what Garbarino means by a “sustainable” society. Here are a few highlights:

I look out over a gentle valley in the Kumoan Hills at the base of the Himalayas. A river flows through the vallye, forming now and again manmade tributaries that irrigate the fertile fields. These fields surround the fifty or so thatched or tin-roofed houses and extend in increasing narrow terraces up the surrounding hillsides.

In several of these fields I watch village men standing on their wooden plows goading on their slow-moving water buffalo who pull the plows, provide the men’s families with milk, and help to carry their burdens. And amid the green of the hills, in brightly colored saris and nose rings, women cut the high grasses to feed the buffalo and gather the firewood which, along with the dried dung from the buffalo, will provide the fire to cook the grains harvested from the fields and to warm the houses against the winter colds and dry them during the monsoons. A huge haystack passes along the path, seemingly self-propelled, in that the woman on whose head it rests is lost entirely from view.

It all moves as if in slow motion. Time is measured by the sun, the seasons, and the generations. A conch shell sounds from a tiny temple, which houses a deity worshiped in these hills. The stories of this and other deities are recited and sung, and they are honored by flowers and festivals and fasts. They provide a context–vast in its scale of aeons of time, rich with teachings of reincarnation and the morality inherent in the inevitable workings of karma. And it is this context that gives vertical meaning to these villagers’ lives with their endless repetition of cycles of birth and death. (p. 36-37)

The Other Side of the Story

This scene is seductive, rich with description of people living in a sustainable society close to the Earth. However, there is another side to this story. It would burst the bubble of the utopians to hear it. Further, it would give great credence to Christianity as a potent force for personal freedom in the world. This alternative account comes from a humble missionary story, The Bamboo Cross (1964), by Homer Dowdy:

Just over beyond the mountains which surrounded the Sixteen Peaks lived the Tring. They were the most difficult of all the mountain tribes that Sau had tried to reach. They were shy. When strangers approached they scurried into the forest. The Tring were the poorest, most fear-ridden tribe of all. If Sau’s people often went hungry, the Tring lived always on the edge of starvation.

They did not live in villages.

The spirits that ruled them forbade one family to dip water from another’s source; one of them could not even live across the stream from an in-law. So Tring houses were spotted sparsely for long distances along the mountain rivers, each a desolation picture of isolation.

Clinging to the steep, stony sides of mountains for mere existence, the Tring shivered in the ceaseless cold of the wind. Often gusts broke down the corn before it could come into ear. The wet monsoon blew when they needed it to be dry, and when it was dry for too long they suffered from the drought.

The demons, too, kept them hungry. If a man went to his field in the morning and found dew on the ground, he returned home without working that day to avoid a curse.

If fortune kept him away from his field beyond the planting season–well, it was evident that the spirits did not want him to find his food in such an easy way.

And if he did plant, he was careful not to plant enough to satisfy his needs. The spirits always demanded of him that he search in the forest for roots and leaves to eke out his diet. For this reason he was inclined to plant just enough mountain rice to keep his alcohol jars full. (p. 72)

The Bamboo Cross is a descriptive account of how people’s lives in this tribe and others were truly transformed when they were released from the spiritual bondage to their demons and fat sorcerers (who exacted large amounts of material goods from their subjects to relieve them of supposed curses).

New Green Utopia

Green Utopia, then, may be a place–several generations hence–where people living in a “sustainable” society strongly resemble more primitive cultures with one notable exception. There will be a little box that does things, and people talk on it, and you have to push the correct buttons for food and medicine. No one knows the complicated math and science required to program this box because shopkeeper math and logic are not taught anymore. The little box is, therefore, an object of great superstition and magic. It accurately predicts the weather and seems to know almost everything.

The little box is the computer.

Garbarino’s book was probably never a best-seller. But for those who are seeking to understand the rationale, worldview and justification for such a radical education reform proposal, it just might provide a few unexpected answers.

|

| 1990 Iowa Department of Education documents with Gaia worship included. See HERE and HERE |

and the fulness thereof;

the world,

and they that dwell therein.”

(Psalm 24:1)

Endnotes:

1. Before Herescope was a blog it was a column in a monthly magazine during the mid-1990s called The Christian Conscience published by Iowa Research Group, Inc. In the months to come we will resurrect some of these original articles and republish them, including many articles that were authored by what is now known as the Discernment Research Group.

2. Copyright Sarah H. Leslie, 2993, 1999, 2019. This article was originally written in June 1993. It was originally published the Free World Research Report and later republished as Appendix XXVII in the original edition of Charlotte Iserbyt’s book the deliberate dumbing down of america (1999). Charlotte’s book is now available as a free download online at http://deliberatedumbingdown.com/ddd/deliberate-dumbing-down/ The Social Studies Horizons newsletter quoted in this article can be found described on pages 275-277 of this book.

3. Before there was a Discernment Research Group it was called the “Iowa Research Group.” From 1989-1999 a group of Christian mothers (and fathers) researched New Age/New World Order elements inherent in education reform plans across America and published their warnings in periodicals, newsletters, and on the Internet. Berit Kjos was one of the foremost researchers and her website www.crossroad.to is a treasure trove of many articles on the history of education reform. See especially her books Brave New Schools and Under the Spell of Mother Earth. Many links in this article go to her website.

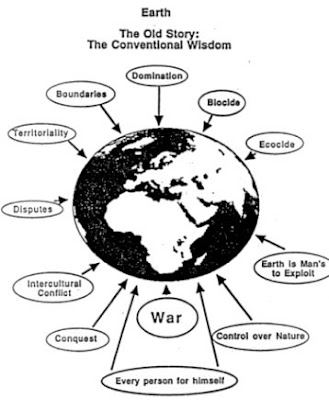

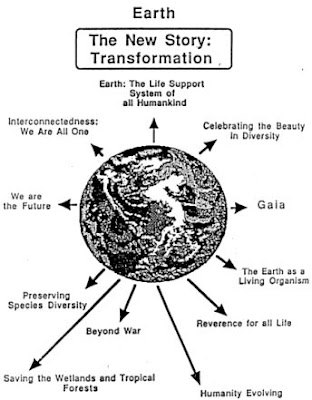

The two cartoons were drawn by a 11 year old Iowa homeschooled boy and were published with the original article.

Several exhibits in this post come from websites concerned with poverty in india.