Jesus, Paul and Midrash[1]

God’s Truth versus Men’s Traditions[2]

This people honoureth me with their lips, but their heart is far from me.

Howbeit in vain do they worship Me,

teaching for doctrines the commandments of men.

For laying aside the commandment of God,

ye hold the tradition of men….”

Emphasis added, Jesus, quoting Isaiah 29:13 in Mark 7:6-8, KJV

Introduction—the Jews and the Oracles

Amidst all the spiritual chaos in the world, ancient and modern, arising from mystics claiming that God has revealed “this or that” to them, the Lord committed His revelation—His “oracles”—to the Jews. After indicting the Jews for having lived hypocritically under the Law, the Apostle Paul rhetorically asked, “What advantage has the Jew?” He then answered, “Great in every respect” because “they were entrusted with the oracles [Greek, ta logia] of God” (Romans 3:1-2, NASB). Moses noted the incomparable nature of God’s revelation to the Israelites when he asked them before entering the Promised Land, “What great nation is there that has statutes and judgments as righteous as this whole law which I am setting before you today?” (Deuteronomy 4:8, NASB). In his book The Gifts of the Jews, Thomas Cahill says that, “The Bible is the record par excellence of the Jewish religious experience, an experience that remains fresh and even shocking when it is read against the myths of other ancient literatures.”[3]

God’s supernatural endowment of Israel with the Torah (the Books of Moses) and the Tanakh (the rest of the Old Testament) distinguishes the Jews from all the other peoples and nations of civilization, whether ancient or modern. Though the Lord gave the Law, the Prophets and the Writings (i.e., the constitutive parts of the Hebrew Bible Jesus recognized, Luke 24:44) for the benefit of the Gentiles, He originally did not give it to the Gentiles. Torah was and is a part of Israel’s peculiar national identity. But from the time of Moses to the Babylonian Exile (for about ten centuries) Israel neither appreciated nor obeyed the Law.

The Babylonian Captivity—

Separated from the Temple

After the Assyrians invaded and took captive the northern kingdom for its disobedience to the Lord (circa 722 BC), God allowed the southern kingdom Judah, because like her sister to the north she continued in rebellion and idolatry (See Jeremiah 25:8-11.), to suffer the same fate by the Babylonians a century and a half later (circa 586 BC). The invaders destroyed the temple and seized the Temple’s holy furniture and furnishings (i.e., the very objects the Lord had designed and commanded to be used in worshipping Him). For seventy years their exile in Babylon would separate the Jews from their homeland and the religious institutions God ordained. Being forced to relocate hundreds of miles to the east by their captors with just the clothing on their backs and the possessions they could carry, the only portable object of their religion was the Torah. During the exile, the Book of the Law would serve as a rallying point for Jewish refugees so that they would be insulated from and not seduced by the spirituality of their pagan captors (i.e., “influences from the east,” Isaiah 2:6, NASB), the very spirituality the Lord commanded Abraham to separate from 1,400 years earlier (Genesis 12:1). As Terry summarizes, “The loss of temple, throne, palace, and regal splendour turned the heart of the devout Jew to a more diligent inquiry after the words of Jehovah.”[4]

In the aftermath of, and perhaps during, the Babylonian Exile, Ezra, a priestly descendent of Aaron, “prepared his heart to seek the law of Jehovah and to do it, and to teach in Israel statutes and judgments” (Ezra 7:10, KJV).

Remember Torah!

So the rallying cry on the part of teachers like Ezra was for Jews to live separate from the religious influences of Babylon and Canaan. But neutralizing that pagan pressure upon Israel would not be an easy task. Far too convenient it was for God’s people to compromise with the religious beliefs and practices of their captors and neighbors. (Read the early chapters of Daniel; See Revelation 17:1-7.) So having survived their seventy-year stay in Babylon and when they were about ready to return to Jerusalem, the Lord told the returning Jews and their spiritual leaders, “Depart ye, depart ye, go ye out from thence, touch no unclean thing; go ye out of the midst of her [i.e., Babylon]; be ye clean, that bear the vessels of the Lord” (Isaiah 52:11, KJV). As did Abraham, the leaders and the people were to separate themselves from Babylon’s idolatry, both literal and mystical.

But upon Israel’s return to the Land, the times were changing, and Torah “had to be fitted to these latter times and [had] to be expanded, and this was done by the process of midrash.”[5] This task of applying the Law to the new cultural situations the Jews encountered would belong to the leadership of the synagogues, the rabbis and elders. So from Ezra’s example of devotion to the law, a Great Synagogue was called (Nehemiah 8:1-15). It was hoped that Ezra’s dedication to the Law would be contagious and inspire commitment among other priests, rabbis and elders to read, study, teach and apply God’s oracles to the lives of the people. At first, the teaching was verbal and would in time, come to be known as “Midrash” (from the Hebrew verb darash, meaning “to seek, study or inquire”). Though difficult to define, Yarchin offers that Midrash is “a Hebrew term for the notoriously hard-to-define rabbinic mode of interpretation.”[6] He continues to tell us that Midrash “almost always involved establishing of connections between the biblical texts by any number of linkages: philological, paronomastic [i.e., word plays], thematic, numeric, historical,” and then adds that, “almost any basis could be employed to shed light from one biblical text upon another.”[7] Whew!

The interpretive expositions of Midrash included two parts.

Keeping Torah Relevant—Halachic Midrash

To adapt and make the Law of Moses relevant for the Jewish people upon their return to Jerusalem as they confronted the legal and spiritual challenges posed by Greek and Roman culture, the rabbis, with Torah as the reference point, gave expositions of the Law and made new applications (i.e., casuistic or case law) to resolve issues, controversies and conflicts that arose. These situational case laws were known as the halakah. In some instances, it was claimed that some of the oral-case laws possessed divine authority because through the centuries they had been handed down by “tradition” from Moses.

Making Tanakh Captivating—Haggadic Midrash

But there was more to the Jewish Bible than just the Law of Moses, or Torah. In addition to the Books of Moses (i.e., Genesis thru Deuteronomy), the Hebrew Scriptures included the books of the prophets and other writings. Jesus spoke of this when He identified the established Old Testament canon to consist of, “the Law of Moses [Torah], the Prophets and the Psalms [Tanakh],” the same thirty-nine books in our Protestant Bibles (Luke 24:44). During the Babylonian Exile and after the return, the rabbis and elders gave sermons based upon individual and isolated texts (atomistic interpretations) in Torah and Tanakh. These sayings/sermons were memorized and collected as other rabbis later borrowed or quoted (“. . .”) from them in synagogue meetings (kind of like contemporary pastors who get their sermons from the Internet). Sermons that were thought worthy (i.e., like today’s “best selling” authors and pastors) were collected and collated and became known as the haggada.

To stimulate obedience to the Law and arouse the feeling and experience of hearing about the Hebrew Scriptures (like many evangelicals today, perhaps the Jews then too were bored with “just” the Bible), the rabbis adopted interpretive techniques to embellish the text’s literal meaning. They mixed “memorable sayings of illustrious men, parables, allegories, marvelous legends, witty proverbs, and mystic interpretations of Scripture events” into their sermons.[8] And as they evolved over time, the haggadim “became more and more complicated as new legends, secret meanings, hidden wisdom, and allegorical expositions were added by one great teacher after another.”[9]

Eventually during the centuries between the prophet Malachi and John the Baptist (the four centuries between the Old and New Testaments when God’s oracles were silent), the Pharisees became the heirs and custodians of “the halachic and haggadic traditions.”[10] In fact one rabbi, Philo (25 BC—40 AD), in Alexandria, Egypt, a contemporary of Jesus, became a chief proponent of midrashic interpretation and exposition as exhibited by his allegorical, even superstitious, handling of the Hebrew Bible. One must ask, “How did this rabbinical belief that Scripture contains mystical/mythical meaning come about?”

The Interface of Judaism with Hellenism

Even though they had returned from Babylon, the Jews could not escape “the influences from the east” that had surrounded them. When the Assyrians conquered Babylon, many of the priests migrated westward. Babylonian spirituality (acclaimed to be the “Gateway of the Gods”[11]) intermingled with Greek civilization, their spiritualities cross-fertilizing with one another even as they threatened the purity of the Jewish faith. In this cultural milieu, rabbis borrowed interpretive methods (i.e., middot) from the Greeks.[12] They began to explain the Jewish Scriptures like the Greeks explained their myths.

To make their incredible myths acceptable to a sophisticated and skeptical intelligentsia, “interpreters turned to allegory to find meanings [for] the Greek myths that would make them acceptable to the educated mind.”[13] Yarchin explains the attitude of the ancient Greeks and Romans toward their own religious writings, that,

The basic interpretive presupposition was this: due to the inherent limitations of human understanding, there will always be something in the sacred text that remains undisclosed to unglossed reading. Mystery then, was characteristic of sacred texts. God is the speaker, but humans are the writers, and multiplicity of meaning (plain and obscure) is to be expected in the discursive space between what the words humanly say and what they divinely teach.[14]

Jewish spiritual leaders began to treat their Scriptures like the Greeks treated their myths. In studying the text, they thought that esoteric or subjective meanings resided “behind,” “in” or “beyond” the markings, words, sentences and numbers of the Hebrew text; that to understand the Bible, the senses of remaz (i.e., hidden meanings), derush (i.e., extensively searched out meanings of allegory or legend), or sod (i.e., mystic or Cabalistic meanings) must be searched out and exposited.[15]

Given the similarity of Midrash to how Hellenists interpreted their myths to make them palatable to audiences, it’s safe to conclude that, in part, Jewish Rabbis borrowed interpretive methods from the Greeks in an effort to encounter and share in “the divine mind” they believed lay behind their Scriptures. By “discovering” allegorical and mysterious meanings behind an otherwise plain text, the teachers believed they could enter into the mind of God, perhaps even entering union with Him. Perhaps this was what Jesus was getting at when He said to the Jews, “You search the Scriptures, because you think that in them you have eternal life….” (John 5:39, NASB).

The midrashic interface of Judaism with pagan Hellenism introduced “the stuff” of allegory, legend and Cabbalistic meanings into the Torah and Tanakh. Important rabbis (but not all) seemed to have succumbed to the Gnostic dictum that, “Truth did not come into the world naked, but in symbols and images.”[16] Paul warned of this dangerous dance with the dialectic when he wrote to the Colossians, “See to it that no one takes you captive through philosophy and empty deception, according to the tradition of men, according to the elementary principles of the world, rather than according to Christ” (Colossians 2:8, NASB).

Halakah + Haggada = Midrash

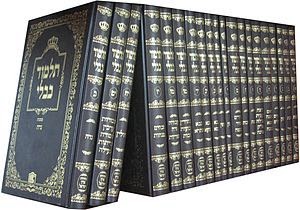

Initially preserved in oral form for several centuries, the midrashim were not finally edited and codified until two centuries after Christ by Rabbi Judah Ha-Nasi (d. circa 217 AD). When codified, both the halakah (the rabbinic expositions of the Law) and haggada (the rabbinic sermons on the Old Testament) came to form Midrash. Today Midrash is a treasury of Hebrew national and folk lore (Hence, the desire of those within the Hebrew Roots movement to study Midrash.)

But returning for a moment to the centuries before Jesus’ life, a major aberration regarding the Midrash developed. During the intertestamental period, the “contextualizations” of the rabbis came “to be placed upon a par with divine revelation,”[17] and by the time of our Lord’s life on earth, the explanatory teachings had grown to become “a fixed and growing supplement to the biblical text, possessing an authority equal to that of the Scriptures [so much for sola scriptura].”[18] As can be observed in Jesus’ interaction with the Pharisees over halakah, this development the Lord Jesus did not accept (Mark 7:1-13; Matthew 15:1-14; 23:1-33).

This background regarding the origin and implications of Midrash brings us to the issue of Jesus’ relationship to it. Regarded by some as “Rabbi,” a title He found superficial (Matthew 23:6-8), it must be asked: “Did Jesus and His apostles’ approve of the Midrash?” or “Did the Lord and the New Testament writers employ midrashic methods of exegesis?” We look first to the Bible for answers and then to scholarly authorities for confirmation of understanding.

Jesus and Halakah-Midrash

The condescending attitude of elitist Jewish scholars toward Jesus is evidenced in the Gospel record when on the occasion of the Feast of Booths (a.k.a., Tabernacles), He went up to and taught in the Temple. Upon listening to the Lord’s words, the response of the Jews (i.e., Jewish leaders) toward Jesus was, “How has this man become learned, having never been educated?” (John 7:15, NASB) Learned in what and educated by whom? The only answer can be, learned in Jewish traditions (i.e., Midrash) and educated in the interpretive methods of the rabbis. So to their question, Jesus tersely replied: “My teaching is not Mine [And by implication not theirs either!], but His [the Father’s] Who sent Me” (John 7:16, NASB). This interchange and clash between Jesus and the leaders of the nation indicates what the Lord thought about the teaching/traditions of the Jews, or the Midrash. Jesus did not teach like the rabbis. To embellish His authority, He did not quote other rabbis (other than to occasionally tell his audiences, “You have heard…”). No, in a manner of speaking, Jesus quoted His Father! Jesus endowed His teaching with the authority of heaven. So, after alluding to a rabbinical teaching (“You have heard…”), Jesus would emphasize, “but I say to you…” (See Matthew 5:22, 28, 32, 34, 39, 44; etc.).

To this point Kaiser warns that the playful rabbinical “search (derash) for the deeper and more exotic meaning [sod] tended to work at cross-purposes with the more sober and literal approach to the text.”[20] Then he points to, as exhibited by many ancient rabbinical sayings, the dialectic affect that mystical-non-literal meanings had upon Scripture’s plain meaning: “Eventually the Sod [esoteric and mystical meanings] overtook the concerns of Peshat [the plain and literal meaning of the text].”[21] In other words, amidst the dialectical exchange between the plain sense of the Bible and a mystical understanding of it, the meaning of the plain text is gobbled up by human imagination. The Bible’s meaning becomes a spiritual Disneyworld. This is the Jewish mindset Jesus confronted during His life and ministry on earth, a mindset corrupted by the allegories of Derash and mysticism of Sod.

Upon reading the Gospel records, one gets the impression that Jesus and the Jews were on different wavelengths (Matthew 13:10-15; Acts 7:51-53). The clash may be accounted for by reason of the prevailing Midrash-mindset of the Jewish leaders and their followers. The whole enterprise of Midrash may be behind Jesus’ words to the Jews (to cite the text again) when He said: “You search the Scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life; it is these that testify about Me” (John 5:39). Apparently, the Jews were more interested in Midrash than the Messiah. This is perhaps why in the end, they rejected Him. They could not accept that the “literal” Scriptures testified of Him. There were other more captivating meanings to be found in the text.

On a few occasions the Lord directly condemned halakic interpretations. Once He told Jewish leaders:

(Emphasis added, Jesus, quoting Isaiah 29:13 in Mark 7:6-8, KJV; Compare Matthew 15:1-10; 23:16-24.)

Some might dispute that Jesus specifically attacked halakic Midrash. But Lane’s comments on Jesus’ words enforce the point. He wrote:

Jesus’ sharp rebuttal sets in radical opposition the commandment of God and the halakic formulations of the scribal tradition. Theoretically, the oral law was fence which safeguarded the people from infringing the Law. In actuality it represented a tampering with the Law which resulted in distortion and ossification of the living word of God. The exaggerated reverence with which the scribes and Pharisees regarded the oral law was an expression of false piety supported by human precepts devoid of authority. Jesus categorically rejects the authority of the oral [then halakic-midrash] law.[22]

In defending the use of Midrash, there are those who suggest that Jesus employed the method. But such an opinion places Jesus in conflict with Himself. How can He on the one hand criticize the Jews for conjuring up halakic–Midrash on the Torah and then turn about and embrace the same? No, as is evident in His words to and about the Pharisees, Jesus would have none of that. His words were different and set apart from the Rabbis’. As one Old Testament scholar notes, “Jesus gives us no examples of midrashic… exegesis.”[23] Kaiser then explains that, “It is likewise doubtful that one can find an allegorical approach in Jesus’ use of parables” because they are “direct analogies rather that the more indirect allegories.”[24] We turn to the Apostle Paul. What was his attitude toward Midrash?

Paul and Midrash Halakah/Haggada

On a number of occasions, the Apostle Paul describes false teachings which obscure the Gospel and deceive people as

- “tradition (paradosis—a giving over by word of mouth or in writing)[25]…

- fables (muthos—a fiction, a fable, an invention, a falsehood)…

- endless genealogies (genealogia—inconsequential and embellished records of descent or lineage)…

- profane and vain babblings (kenophonia—words which captivate hearers by “sound” rather than truth)…

- oppositions of science (antitheseis tēs pseudōnymou gnōseōs—Gnostic beliefs sourced in mystery which contradict the apostolic faith)…

- Jewish myths (’Ioudaikois muthois—fictions, fables which are distinctly Jewish in their origin)… [and]

- commandments of men (entolais anthropon—commandments which originate with man, not God).”

(See Colossian 2:8; 1 Timothy 1:4; 6:20; Titus 1:14.)

Once at the beginning and then again at the end of his first letter to Timothy, Paul warned him not to “give heed to fables and endless genealogies” (1 Timothy 1:4), and to avoid “profane and vain babblings, and oppositions of science falsely so called” (1 Timothy 6:20). As regards the meaning of Paul’s caution to young Timothy, J.N.D. Kelly (1909-1997) commented that because of the letter’s Jewish background,

the fables and genealogies must have had to do with allegorical or legendary interpretations of the O.T. centring on the pedigrees of the patriarchs. Much of the rabbinical Haggadah consisted of just such a fanciful rewriting of Scripture; the Book of Jubilees and Pseudo-Philo’s Liber antiquitatum biblicarum, with its mania for family trees, are apt examples. It has also been shown that in post-exilic Judaism there was a keen interest in family-trees, and that these played a part in controversies between Jews and Jewish Christians.[26]

Kelly then concludes that, “Viewed in this light the errorists are Judaizers who concentrate on farfetched minutiae of rabbinical exegesis to the detriment of the gospel.”[27]

Paul also warned Titus, who ministered on the island of Crete, about dealing with the opposition posed by “many rebellious men, empty talkers and deceivers, especially those of the circumcision” (i.e., Jews, Titus 1:10). After informing Titus of the motives, message and methods of these false teachers (Titus 1:11-13a), Paul tells the young pastor to resist and correct the false teachers by reproving “them severely so that they may be sound in faith, not paying attention to Jewish myths [haggadic mysticism?] and commandments of men [halakic legalism?] who turn away from the truth” (Emphasis added, Titus 1:13b-14). We can note that the adjective “Jewish” modifies both “myths” and “commandments.” Paul is warning Titus about Jewish myths (stories, legends, etc.) and Jewish commandments that did not come from God, but originated in the rabbinical mind. As such, the extra-curricular myths and commandments have nothing whatsoever to do with the Christian faith. By the testimony of scholars, we have seen that Midrash contains myths and commandments that interface and intermingle with expositions of Holy Scripture. Presumably then (What else could it be?), is Paul telling Titus to pay no attention to Midrash haggada (“myths”) and halakah (“commandments”).

Sidebar Issues

Issue # 1:

Seemingly, the way Midrash originated and was later formulated finds analogy in how liberal source criticism accounts for the origin of the biblical books. Source critics assert that after their oral introduction, numerous authors over generations redacted and revised various “traditions” of the biblical books. Source critics contend multiple authors redacted the Pentateuch (at least four, JEDP, and maybe more), Isaiah (perhaps three), Daniel and other Old Testament books. (I do not believe this. Like Jesus, I accept that one man, Moses, authored the Pentateuch.)

Turning to the Gospel record, liberal scholars suppose that the record of Jesus’ life was based upon His sayings collected in a fictional source named “Q”. (Again, I do not believe this.) Perhaps the sayings of “Q” were originally oral and became written—who knows for sure? The theory goes that these sayings or “Q” lay behind the writing of the Gospels. So the critics propose that in writing his Gospel, Mark borrowed sayings from “Q” even as later redactors would revise his gospel by inserting other traditions about Jesus’ life into the account. In writing his Gospel, Matthew borrowed from “proto-Mark” and “Q” even as He inserted his “slant” (other sayings, miracle accounts, etc.) on Jesus’ life into his interpretation of Jesus’ life. The historian Luke consulted sources, but he tells readers he did so (Luke 1:1-4). Then you have John (though not one of the Synoptic—“through the same eyes”—Gospels) whose Gospel seems to be a more mystical meditation upon the life of Jesus (i.e., Sod). So in the manner of their composition, Mark becomes a sort of midrash on “Q”; Matthew on “proto Mark” and “Q”; with John supplying a more mystic flavor to his account of Jesus’ life. When it is understood how Midrash historically developed, its development becomes a “cue,” even template, for how liberal source critics account for the origin of the Gospels. After all, that was how the Talmud developed, how Judaism embellished, refined and finally codified its inherited “traditions.” Why not the New Testament? Its authors were, after all, overwhelmingly Jewish.

Issue #2:

Is there a meaning in the text? Midrash seems to have indiscriminately blended together the Word of God and the word of men, and in many instances, made them equal. Yet there are those within pan-evangelicalism who suggest that to understand the Bible, we need to shuck our western Greco-Roman mindset and immerse ourselves into the Hebrew way looking at Scripture. Because Jesus and the apostles were Jews, to understand the Christian faith we need to enter into a Jewish understanding of it. For such entrance, a study and knowledge of Talmud (which contains Midrash) is deemed necessary.

Some emergent church leaders argue that Paul’s message was too “Greekish” (i.e., western in orientation). They contend that a western mindset (with its creeds, rituals, liturgies and so forth) has deformed Christianity.[28] The Hebrew Roots Movement also views that “western-ism” has infected the Christian church, and that only deep attention to Christianity’s distinctly Hebrew heritage (which presumably involves knowledge of Midrash and Talmud) can cure it. Both “emergent” and “roots” movements seem to ignore that overemphasis upon the “Hebrew-ness” of Christianity could diminish appreciation for the ministry and message of the Apostle Paul who after all, was “an apostle to the Gentiles” (Galatians 2:8; Romans 11:13), and the one in whom the Lord placed custody of the Gospel.[29] In fact, Paul’s letters of Galatians and Ephesians argue against becoming too Hebrew in understanding Christian faith. The irony of today’s advocacy for a returning to “the Hebrew mindset” is that the Jewish cultural milieu in which Christianity was birthed—the intertestamental period—was corrupted by the Greek methods of interpreting and understanding divine oracles!

Those who argue that the apostles contextualized their message via the methods of Midrash cite Matthew’s citation of Hosea as an example. Referencing the Exodus motif, that Gospel compared Jesus’ sojourn in Egypt to escape Herod’s murderous design upon Him with the quotation, “Out of Egypt I called My Son” (Matthew 1:15 and Hosea 11:1). Without developing the argument, I would simply note two points: first, there is no ancient Jewish literature which contains a typology of the Messianic exodus like Matthew’s (the reference is particular only to this apostle)[30]; and second, by referring to the Exodus motif, Matthew simply reminded his readers that as God sovereignly and providentially protected Israel His “firstborn” in Egypt (Exodus 4:22), so He protected Jesus.

Conclusion

As a corrective to the Judaism of Hellenism, we have seen that neither Jesus nor the apostles offered midrashic interpretations. Jesus disapproved of exchanging Yahweh’s Tanakh (The Jewish canon Jesus quoted, approved of, and said bore witness to Him!) for men’s traditions (Mark 7:8). The Apostle Paul—who underwent rabbinical training and testified he had been “extremely zealous for [his]… ancestral traditions” (Acts 22:3; Galatians 1:14)—warned Timothy and Titus about the imagined myths and the invented commandments of Judaism (1 Timothy 1:4; 6:20; Titus 1:14). Frankly, if both Jesus’ condemnation of and Paul’s warning about “traditions” do not either in part or the whole refer to the oral or written Midrash, then it’s difficult to know historically what they were warning about.

For a moment and for the sake of argument, let’s assume that Jesus and the apostles commonly employed midrashic methods (other than mostly literal, or peshat) in their Old Testament citations and expositions regarding His ministry and life. When applied to an understanding of the biblical books, how does a midrashic hermeneutic (borrowed from the way the Greeks sought to understand their sacred writings) affect the perceived meaning, especially prophetic, residing in the words of the text? Shepherd observes that if a non-literal meaning is assumed to lay behind the plain text (i.e., allegorical, legendary, Cabbalistic, etc.), a new problem presents “itself in relation to the literal sense of Scripture.”[32] He notes of the problem that, “If New Testament writers depended on nonliteral interpretations, then their interpretive techniques contradicted the norm of ‘the literal sense’ as the only basis for arguments about doctrine and failed to make any compelling case for prophetic fulfillment.”[33] In an internal and contradictory way, any “literal sense as the norm of theological interpretation” would seem to be “ignored within Scripture itself, by its own earliest Christian interpreters of the Old Testament.”[34]

Even if it might seem that an apostle employed a midrashic method in his exposition of Jesus’ life, fine biblical scholars note that,

Where their [the apostles’] interpretations seem to parallel methods of their Jewish forbearers, their uses generally appear extremely restrained. We cannot lump together the apostles, the Qumran exegetes, and the rabbis as if they all operated in the same way. The NT writers borrowed some methods of their Jewish counterparts, but they spurned others.[35]

A Jewish mindset intruded upon by Hellenism’s non-literal allegorical and mythological approach to sacred oracles may, in part, explain why the Jews had so much difficulty in accepting Jesus’ words at face value. Their concept of Messiah was lost in mystery and myth, not unlike liberal scholarship’s denigration of accounts of Jesus’ miracles to have been mythical additions by wishful redactors.

Thus understanding Scripture, to borrow from Churchill’s assessment of Russia, is reduced to “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” And with interpretive layers like that, who could ever with any assurance understand the text’s meaning. Is there not a word from God for the simple man? This may explain why Longenecker admitted that, “we cannot possibly reproduce the revelatory stance of pesher interpretation, nor the atomistic manipulations of midrash, nor the circumstantial nor ad hominem thrusts of a particular polemic of that day—nor should we try.”[36] This also is why Milton Terry wrote: “The study of ancient Jewish exegesis is, therefore, of little practical value to one who seeks the true meaning of the oracles of God.”[37]

specially they of the circumcision . . .

Wherefore rebuke them sharply, that they may be sound in the faith;

Not giving heed to Jewish fables,

and commandments of men,

that turn from the truth.”

Emphasis added, Paul to Titus, Titus 1:10, 13b-14, KJV

Endnotes:

1. For a fuller picture of how the Bible is being interpreted today, readers are invited to peruse previous posts which are: Larry DeBruyn, “‘Deliteralizing’ the Bible from Plato to Peterson: Scripture amidst the Shadows,” Guarding His Flock Ministries, January 3, 2012 (http://guardinghisflock.com/2012/03/01/deliteralizing-the-bible-from-plato-to-peterson/#more-2038); “‘Babylon Rising’ and Canon in Crisis: Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, Fresh Revelations, and an ‘Open’ Canon,” Guarding His Flock Ministries, January 27, 2013 (http://guardinghisflock.com/2013/01/27/babylon-rising-and-canon-in-crisis/#more-2365).

2. MIDRASH IN THE MAZE: The Midrash (from the Hebrew verb darash, meaning “to seek, study or inquire.” The noun occurs in 2 Chronicles 13:22 where the historian states: “Now the rest of the acts of Abijah… are written in the midrash of the prophet Iddo,” and 2 Chronicles 24:27 which refers to what is written “in the midrash of the Book of the Kings.”) Midrash refers to the earliest and ancient exegetical expositions of the Hebrew Bible given by Jewish rabbis and elders spanning the seven or so centuries following the Babylonian Captivity (circa 500 BC) until two centuries after Christ (circa 200 AD). Midrash is composed of two parts: first, the halakah which refers to the rabbinical interpretations and applications of the Law or Torah; and second, the haggada which refers to the collected sermons of rabbis on Tanakh, the name assigned to the rest of the Hebrew Bible. (Tanakh includes Torah, but Torah does not include Tanakh.) Together, parts of the oral Midrash—depending upon which traditions and sermons the rabbis thought worthy—were through the centuries edited, modified and collected as they grew to comprise the “written” Mishna. In the centuries following, rabbis developed additional commentary upon the Mishna which became known as the Gemara. Together, the Mishna and Gemara comprise Talmud. So Midrash refers to the earliest oral interpretations given by rabbis in ancient synagogues on Tanakh generally (i.e., haggada) and Torah especially (i.e., halakah).

I offer this above overview with the knowledge that Midrash is as Yarchin writes, “a Hebrew term for the notoriously hard-to-define rabbinic mode of interpretation.” See William Yarchin, History of Biblical Interpretation: A Reader (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc., 2004): xvi. Yarchin observes that according to midrashic interpretation, “understanding the Bible more authentically resides, perhaps strangely, in the uncertainty of its interpretation, never fully finished.” (xvii) In a way, the activity of midrash illustrates (to for a moment engage in midrash) what Paul wrote about when he described the opponents of Moses, Jannes and Jambres, as men who were “always learning and never able to come to the knowledge of the truth” (2 Timothy 3:6-7).

3. Thomas Cahill, The Gifts of the Jews: How a Tribe of Desert Nomads Changed the Way Everyone Thinks and Feels (New York, NY: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1998): 6. I disagree that the Bible is only a record of “the Jewish religious experience.” It goes beyond that mystical dimension. While God’s salvific work includes a divine encounter with His word, it is neither parochial to nor exhausted by human experience. The biblical record is one of God’s sovereign and providential dealings with the world through the Jewish people, which divine workings were preliminary to the incarnation of Jesus Christ, culminated in His penal substitutionary death on the cross and resurrection from the dead, and will conclude with the Lord’s future return and reign on earth. Genuinely spiritual experiences are neither self-induced nor insular because humans respond for reason of the Holy Spirit’s initiation of the experience (John 3:4-8). In other words, no God no divine experience, only “religion.”

4. Milton S. Terry, Biblical Hermeneutics: A Treatise on the Interpretation of the Old and New Testaments (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, n.d.): 604.

5. Hermann Leberecht Strack, “Midrash,” The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Volume VII, Samuel Macauley Jackson (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, Reprint 1977): 366-370.

6. Yarchin, History of Biblical Interpretation, xvi.

7. Ibid.

8. Terry, Biblical Hermeneutics, 609.

9. Ibid., 608.

10. “The central concept in rabbinic exegesis, and presumably that of earlier Pharisees as well, was ‘midrash’.” See Richard N. Longenecker, “‘Who is the Prophet Talking About?’ Some Reflections on the New Testament’s Use of the Old,” Themelios 13.1 (Oct. / Nov. 1987): 6.

11. Anton Gill, The Rise and Fall of Babylon: Gateway of the Gods (London: Quercus Publishing Plc, 2011).

12. Let it be stated that not all of the interpretive guidelines (i.e., middot) established by the rabbis are to be faulted. For example, peshat, which to the rabbis was/is the clear, simple, plain, literal and historical meaning of the text (the objective meaning) can be agreed to by most Bible teachers and scholars.

13. Yarchin, History of Biblical Interpretation, xii.

14. Ibid.

15. The Jews also used pesher (“this is that” which Isaiah predicted) as a method to interpret Old Testament prophetic passages. The method was employed especially by the Qumran community as they believed they were living at the end of days. This method of exegesis is not unlike those peddling the novel post-modern prophecy paradigm who find exotic and puzzling new meanings in the Bible which they then attempt to buttress by citing other ancient but non-canonical writings, i.e., Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, etc. For an evaluation of how one rabbi uses pesher interpretation in our modern world, see my review of the best-selling book, The Harbinger. Larry DeBruyn, “The Harbinger: A Review and Commentary,” Guarding His Flock Ministries, June 9, 2012 (http://guardinghisflock.com/2012/06/09/the-harbinger/#more-2144).

16. Marvin Meyer, “The Gospel of Philip,” The Gnostic Gospels of Jesus: The Definitive Collection of Mystical Gospels and Secret Books about Jesus of Nazareth (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 2005): 67.

17. Moisés Silva, “Has the Church Misread the Bible?” Foundations of Contemporary Interpretation: Six Volumes in One (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1996): 77.

18. Emphasis added, Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., “A Short History of Interpretation,” An Introduction to Biblical Hermeneutics: The Search for Meaning (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1994): 212.

19. “Authority” of other writings beyond “the Jewish oracles” recognized and preauthorized by the Lord Jesus Christ characterizes other religions (Islam), cults (Book of Mormon) and the Roman Catholic Church (The Pope speaks in the voice of God, ex cathedra). The mystical addiction of looking to writings other than the Bible for spiritual illumination, even on the part of evangelicals, is difficult to rehabilitate. Everybody wants “something more… I need… I need… I need.”

20. Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., Toward an Exegetical Theology: Biblical Exegesis for Preaching and Teaching (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1981): 55.

21. Ibid.

22. William L. Lane, The Gospel of Mark (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1974): 248-249.

23. Kaiser, Jr., “A Short History of Interpretation,” 217.

24. Ibid.

25. In the Colossian context, “tradition” in Colossians 2 verse 8 may refer not only to the teaching of a Gentile false teacher but likely also to a Jew who drew “on Jewish magical and mystical traditions [i.e., like those that form a part of Midrash].” See Clinton E. Arnold, The Colossian Syncretism: The Interface between Christianity and Folk Belief at Colossae (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1996): 209-210.

26. J.N.D. Kelly, A Commentary on the Pastoral Epistles (New York, NY; Harper & Row, Publishers, 1963): 44-45. It ought to be noted that Kelly was an expert in the milieu which surrounded the New Testament era ancient church history.

27. Ibid, emphasis added.

28. Emergent church leader Brian McLaren makes this point when he wrote: “If we locate Jesus primarily in light of the story that has unfolded since his time on earth [according to the Greek-Roman western mindset], we will understand him one way. But if we see him emerging from within a story that has been unfolding through his ancestors [according to a eastern Hebrew-Jewish mindset], and if we primarily locate him in that story, we might understand him in a very different way.” See Brian D. McLaren, A New Kind of Christianity: Ten Questions that are Transforming Faith (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2010): 36-37.

29. See Larry DeBruyn, “Apostatizing from the Apostle: Oh, and by the Way, from Jesus Too!” Guarding His Flock Ministries, April 2, 2010 (http://guardinghisflock.com/2010/04/02/apostatizing-from-the-apostle-2/#more-923).

30. Craig L. Bloomberg, “Matthew,” Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament, G.K. Beale and D.A. Carson, Editors (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007): 9.

31. This is but one of other analogies or types in this quotation which remind us of God’s care for and work on behalf of His children (Romans 8:28).

32. Gerald T. Shepherd, “Biblical Interpretation in the 18th & 19th Centuries,” in Historical Handbook of Major Biblical Interpreters, Donald K. McKim, Editor (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1998): 265.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid.

35. Dr. William W. Klein, Dr. Craig L. Blomberg, and Dr. Robert L. Hubbard, Jr., with Kermit A. Ecklebarger, Consulting Editor, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation (Dallas, TX: Word Publishing, 1993): 129. Kaiser cites Frederic Gardner (1822-1889) when he made the same point. He wrote: “In all quotations which are used argumentatively, or to establish any fact or doctrine, it is obviously necessary that the passage in question should be fairly cited according to its real intent and meaning, in order that the argument drawn from it may be valid. There has been much rash criticism of some of these passages, and the assertion has been unthinkingly made that the Apostles, and especially St. Paul, brought up in rabbinical schools of thought, quoted Scriptures after a rabbinical and inconsequential fashion. A patient and careful examination of the passages themselves will remove such misapprehension.” See Kaiser, “A Short History of Interpretation,” 218, citing Frederic Gardner, The Old Testament and New Testament in Their Mutual Relations (New York, NY: James Pott, 1885): 317-318.

36. Longenecker, “‘Who is the Prophet Talking About?’” 4-8.

37. Terry, Biblical Hermeneutics, 609.